Hyding in Music

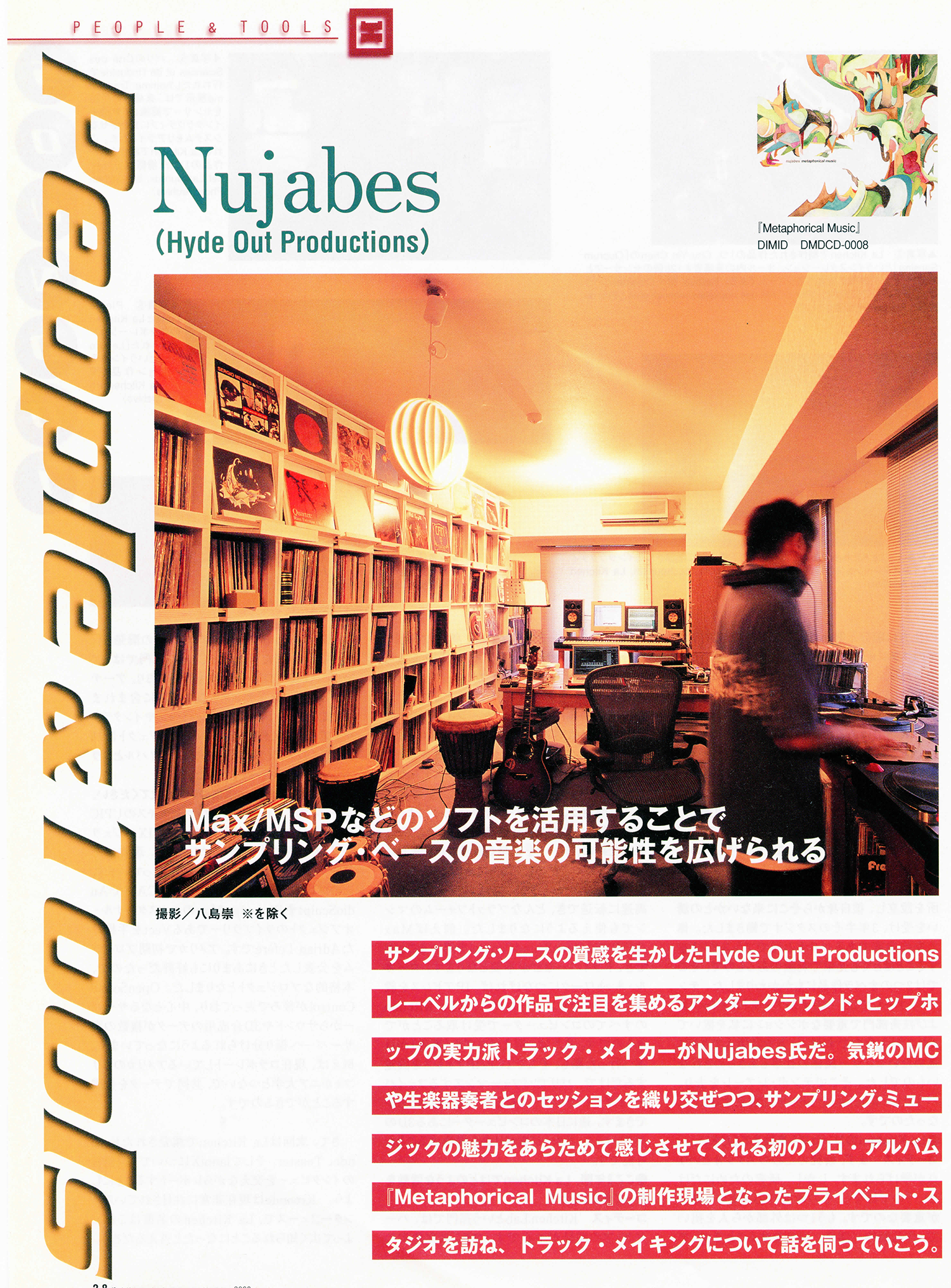

Nujabes in his studio. Photographed by Yosuke Moriya.

Source: Bandcamp

Always being compared to J Dilla could be seen as both an honor and sort of a disservice to Nujabes - a little bit like a Mozart/Salieri type of situation if you will. If Salieri was a fan of Mozart and lived on another continent – you get it. Not to say that the influences, as well as the parallels, are not clearly there. The man likely had one of those at a time ubiquitous “J Dilla Changed My Life” shirts. They share a birthday, both unfortunately passed away in their creative primes (both in February) and both probably became more widely famous and revered posthumously in comparison to their lifetime. They both were pioneers in the hip-hop sub-genre they operated in and are icons within those communities to this day. Whether you call it lo-fi beats, chill-hop, chillwave, or “beats to study to”, Nujabes had a profound influence on a specific aesthetic of beat-making. Years after he produced his own work, that style became quite popular in the form of 24h YouTube streams with looped gifs of Studio Ghibli characters studying. Sometimes the beats in those playlists do their predecessors justice, sometimes they feel like a more washed down and formulaic version. In my opinion, reducing Nujabes’ work to “background music” would be highly inaccurate.

““An SP-1200, MPC, they each have a specific sound to the machine. Combine that with sampling from vinyl and no proper mix on the song, Voila! You get “lo-fi.” Record crackle and whatnot. So, it wasn’t necessarily the artists trying to make their stuff sound dirty, grimy, lo-fi. At the time, that’s what was available and learning how to mix you probably had to go to school for. These were complete do it yourself times. If you don’t have a proper engineer to mix your songs then it’s going to sound lo-fi, or rather, what they call lo-fi now.”

- Pase Rock on “lo-fi””

As a student of hip-hop, Jun Seba got his start in the music business when he opened Guinness Records in Shibuya. According to Pase Rock, a close personal friend, the shop was “the underground hip-hop spot. [It] leaned more towards stuff you’d sample, and underground hip-hop. Soul, jazz, lots of stuff like that. 60% underground hip-hop, 40% other. Jun didn’t really like the commercial hip-hop, so if it wasn’t like DJ Premier, Pete Rock, or Five Deez, he wasn’t with it.” Shortly after opening the shop, he started producing beats himself and founded his record label Hydeout Productions. One of his first (bootleg) vinyl releases was an unofficial remix of Nas’ iconic Illmatic cut One Love in 1998. To promote his music and attract some attention he put copies of his remix within the Nas section of his record shop and had people wondering who this Nujabes guy was. The release of a 36-track mixtape called Sweet Sticky Thing ~Reload All Good Music From Old To The New~ followed within the same year. Long-time collaborator Funky DL says that Nujabes was “very selective in what would be released, even though he’d record a lot of songs. Just about how he felt about the recording at the time, that’s what dictated the recordings being released, or shelved.”

Jun’s rise to popularity within the hip-hop scene can be attributed to his skill of finding obscure samples that fit his methodology of applying warm and emotive sounds with an eastern sensibility for melody. He also implemented hip-hop-atypical instruments like the flute into his music. While many of his beats are rather slow, he did not shy away from more up-tempo speeds on several slightly more experimental tracks that are almost bordering house music. Compared to many other hip-hop productions at the time, a Nujabes beat was always very melodic and provoked an emotional reaction beyond the appreciative on-beat head-nodding. Maybe his biggest talent was his ability to identify the emotional value carried in the samples he digged and amplifying them. May that be melancholy, anguish, joy, or a sense of clear serenity. He always did it with a definitive sense of artistry and appreciation for the beauty of his source material.

In hindsight, many of his beats seem fitting as themes for moody anime openings or endings. So today it does not seem like a surprise that Shin’ichirō Watanabe recruited him to work on the now-cult anime series Samurai Champloo in 2003. It is set in an alternate Edo–era Japan, where samurais and tea houses coexist alongside graffiti tagging and east–coast hip-hop. The plot follows three outcasts trying to track down a mysterious “samurai who smells of sunflowers.” As the director of the classic Cowboy Bebop series, Watanabe already showed that he puts a lot of importance scores and soundtracks. (If you are not familiar with Comboy Bebop’s opening theme song Tank! by Yoko Kanno and Seatbelts, make sure to check out the opening sequence as well as the whole song.) When he came up with the idea of a samurai-hip-hop crossover he “needed someone to take care of the soundtrack” and got introduced to Nujabes via mutual friends. Between the releases of his two solo albums, Metaphorical Music and Modal Soul, Jun worked together with Fat Jon to create the anime’s OST.

Samurai Champloo opening screen grab

Source: bandwagon

The success and international reach of the series granted Jun a boost in popularity in hip-hop scenes worldwide and lead to many young producers trying to emulate the relaxed beat aesthetics they heard on the soundtrack. In my case, Samurai Champloo was probably the only occasion I started to watch an anime series - or any other TV show - for the music only. I was not disappointed in any way.

On February 26th, 2010 Jun Seba, died shortly after being involved in a car accident. He had released only two solo albums - a third in the works, which was finished by a group of his friends.

Metaphorical Music (2003)

metaphorical music cover artwork by Syu

Source: amazon

As debut albums go, Metaphorical Music laid the foundation for all of Nujabes’ musical output in consequence. It is a milestone in lo-fi, jazzy, and melodic hip-hop-production. Nujabes puts precise drums and driving baselines on strictly-from-vinyl samples by Pharoah Sanders, Miles Davis, or Yusef Lateef among others. A lot of horn sounds, dreamy pianos in combination with strings and a plain honest approach creates soundscapes that are so atmospheric, that I almost would have preferred Metaphorical Music to be an instrumental album. Not that the verses contributed by numerous friends and collaborators are plain bad. But for me, some lyrics cross the line into cringe territory at times as they try hard to be conscious and substantial while they rather seem more like technical “rap exercises”. Maybe it is also caused by the mixing, but the beats always feel like the starring cast-member anyway.

Modal Soul (2005)

Nujabes - modal soul Cover

Source: last.fm

After working with Fat Jon on the Samurai Champloo OST, Nujabes started learning how to play different instruments like the trumpet or the flute and made a lot of music with, fellow producer and jazz musician Uyama Hiroto. The album that was created in this time of musical exploration is my personal favorite Nujabes record. On Modal Soul the big influence of jazz is very present again with Jun sampling the likes of Yusef Lateef or Chet Baker. But he also manages to keep finding samples in slightly more obscure places like the progressive-rock band Gypsy, Brazilian singer Nana Caymmi, or composer Noriko Kose for example. Stylistically you still get a beautifully produced, chilled beat album with some rap parts sprinkled throughout and at times with a little bit more dance-music-aesthetics put in the mix. It might be a little slower and smoother in my opinion and appears to have a clearer mastering than Metaphorical Music. I would attest Modal Soul a higher degree of musicality and argue that it is even more soulful (no pun intended) than its predecessor. A logical and improving step forward – just a fantastic second album overall.

Spiritual State (2011)

Nujabes - Spiritual State cover

Source: YouTube

When Jun Seba passed away, his third solo album Spiritual State was allegedly about halfway finished. To honor his legacy and make sure the last Nujabes productions would see a proper release, his close friend Shingo gathered some collaborators from over the years in his studio with the mission to finish the album and do it justice. Not an easy task as Funky DL recalls: “It took a really long time to figure everything out. Even something as simple as what you hear as a piano, it would have to be matched. Music programs these days, you can open a window and there’s 50 piano sounds, so which one is it? A hard sound, soft sound, a more sustained or subtle sound.” Although it slightly lacks some of the finesse of the two previous albums and might not be the “best” Nujabes album per se, it feels – for lack of a better term – more spiritual. Maybe that is simply autosuggestion working its magic, but I can’t help but feel a little moved while listening to this album. While other posthumous album releases can easily give the impression of a cash grab, Spiritual State succeeds in honoring a musical legacy with genuine intentions.

Hydeout Productions logo. Drawn by Nujabes.

Source: RA

Sources:

https://jeff.kim/seba-jun/

https://thehundreds.com/blogs/content/melodies-for-the-soul-remembering-nujabes

https://www.34st.com/article/2018/03/samurai-champloo-nujabes-anime-chill-hip-hop-jazz-samples-music-album-review

https://www.intermissionbristol.co.uk/music/2016/11/10/nujabes-the-j-dilla-of-japan

https://medium.com/auralgrove/seba-juns-nujabes-influence-on-the-current-decade-4e4f461fe573

Thumbnail image: Nujabes in his studio

Source: Jeff Kim